Twenty thousand years ago the world was closed in a great ice age. Ice sheets two miles thick covered most of North America, Scandinavia and the British Isles.

Greenhouse gas concentrations were much lower, the world was 6°C cooler, and because of all the water trapped in the ice sheets, the sea was at least 120 meters lower, exposing land that is submerged today. It would have been possible to walk from France to London via Doggerland or from Russia to Alaska via Beringia.

But our research, now published in Nature, has revealed at least one surprise in the Ice Age climate: The Gulf Stream, which carries warm water north through the Atlantic, was stronger and deeper than it is today. .

This research came about because as paleoceanographers (scientists who study the oceans of the past), we wanted to understand how the oceans behaved during the last ice age to provide insights into how climate change might change things in the future.

Warm water – from Mexico to Norway

Today, warm, salty water from the Gulf of Mexico flows northward as part of the Gulf Stream. As part of it passes through Europe, it releases a lot of heat, keeping the climate of Western Europe very mild.

Tooth et al (2023) Autorea Preprints / WHOI Creative Studio

Then, as the surface water passes north of Iceland, it loses enough heat to increase its density, causing it to sink and form deep water. This process starts the global deep-water conveyor belt, which connects all the world’s oceans, slowly moving heat around the planet to depths greater than a mile below the surface.

Scientists previously thought that the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation — a complex system of deep and surface ocean currents, including the Gulf Stream — was weaker during extreme cold periods, such as the last ice age. In theory, more sea ice in the Arctic would have reduced the amount of water sinking from the surface into the deep ocean, slowing the global deep-water conveyor belt.

However, our new study reveals that the Gulf Stream was actually much stronger (and deeper) during the last ice age. This is despite the prevailing cold glacial climate and the presence of large ice sheets around the northern parts of the Atlantic.

In fact, our research suggests that the glacial climate itself was responsible for driving a stronger Gulf Stream. In particular, the ice age was characterized by much stronger winds over parts of the North Atlantic, which would have driven a stronger Gulf Stream. Therefore, although the amount of water sinking from the surface to the deep ocean was reduced, the Gulf Stream was stronger and still transported a lot of heat northward, though not as far as today.

Reconstruction of past ocean circulation

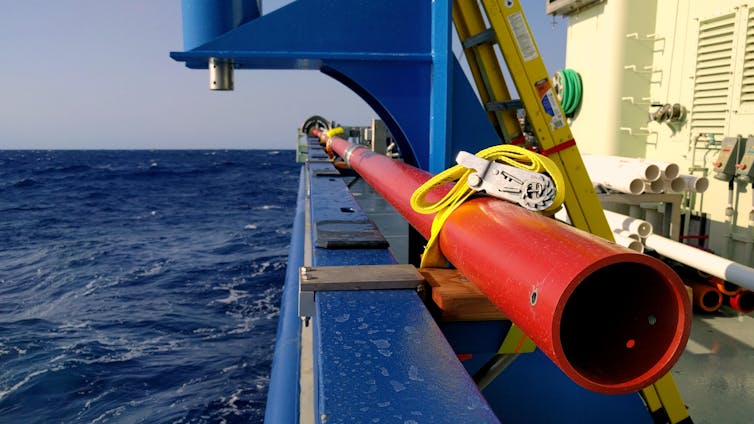

Since we have no data from weather buoys or satellites, we instead reconstructed how the ocean would have circulated in the last ice age using representative evidence preserved in marine sediment cores, which are long mud tubes. from the bottom of the ocean.

The cores we used contained mud that had been building up on the seafloor for the past 25,000 years and were taken from multiple locations along the US East Coast using research vessels from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts, where some of our team is based.

Christopher Griner / Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

To determine the strength of the Gulf Stream during the ice age, we measured the size of the sediment grains within the mud, with larger grains indicating faster flow and vice versa.

From the same mud, we also measured the chemical composition of the shells of tiny single-celled organisms called foraminifera. By comparing data from a range of depths at multiple sites in the Northwest Atlantic, we were able to identify the boundary between those foraminifera that once lived in warm subtropical waters and those that lived in colder subpolar waters. This allowed us to determine the depth of the Gulf Stream at the time those organisms were alive.

This adds uncertainty to climate predictions

Our research highlights how the Gulf Stream, and the wider Atlantic current system, is sensitive to changes in wind strength, as well as meltwater from the Greenland ice sheet. This has important implications for future climate change.

Climate models predict that the Gulf Stream will weaken during the 21st century, in part due to reduced wind. This would lead to even higher sea levels along the US East Coast and relatively less global warming in Europe. If climate change causes changes in wind patterns in the future, the Gulf Stream will also change, adding to uncertainty about future climate conditions.

Our results also highlight why we should not make simplistic statements about Atlantic currents and future climate change. The Atlantic contains a number of interconnected currents, each with its own behavior and unique response to climate change. Therefore, when explaining the impact of anthropogenic climate change on the climate system, we need to be very clear about which part we are discussing and the specific implications for different countries.