Temperature measurement at the outlet opening of the black smoker revealed liquid temperatures greater than 300°C. Credit: University of Bremen

Hydrothermal vents can be found worldwide at the junctions of moving tectonic plates. But there are many hydrothermal fields yet to be discovered. During a 2022 expedition of the MARIA S. MERIAN, the first field of hydrothermal vents was discovered on the 500-kilometer-long Knipovich Ridge off the coast of Svalbard.

An international team of researchers from Bremen and Norway, led by Prof. Dr. Gerhard Bohrmann of MARUM—the Center for Marine Environmental Sciences and the Department of Geosciences at the University of Bremen, now reports on the discovery in the journal Scientific Reports.

Hydrothermal vents are seeps on the sea floor from which hot fluids emerge. “Water penetrates the ocean floor where it is heated by magma. The superheated water then rises back up to the sea floor through cracks and fissures. On its way up the liquid is enriched with minerals and materials dissolved from the rocks of the oceanic crust. These liquids often spill out back to the seabed through pipe-like chimneys called black smokers, where metal-rich minerals are then precipitated,” explains Prof. Gerhard Bohrmann of MARUM and chief scientist of the MARIA S. MERIAN (MSM 109) expedition.

In water depths greater than 3,000 meters, the remote-controlled submersible vehicle MARUM-QUEST took samples from the newly discovered hydrothermal field. Named after Jøtul, a giant in Norse mythology, the course is located on the 500 kilometer long Knipovich ridge.

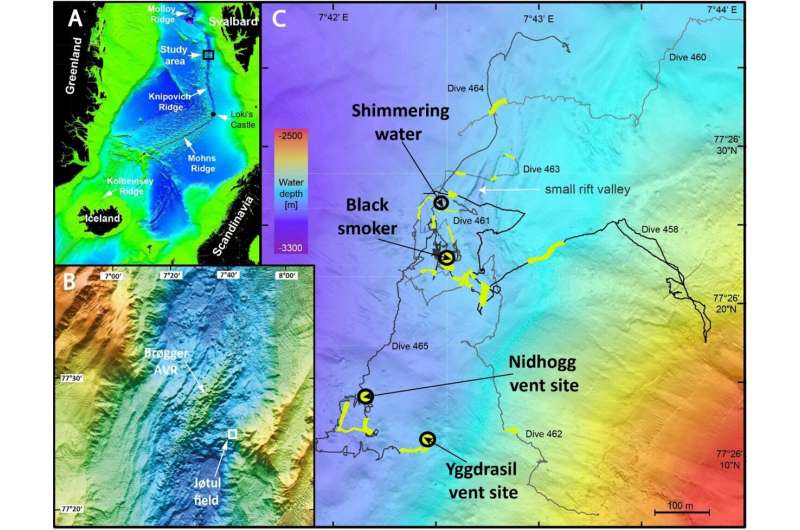

The ridge lies within the triangle formed by Greenland, Norway and Svalbard at the boundary of the North American and European tectonic plates. This type of plate boundary, where two plates move apart, is called a spreading ridge.

The Jøtul field is located on an extremely slow ridge with a plate growth rate of less than two centimeters per year. Because so little is known about hydrothermal activity at slow-spreading ridges, the expedition focused on getting an overview of the escaping fluids, as well as the size and composition of active and inactive smokers in the field.

(A) Map of the Norwegian-Greenland Sea (GEBCO data) with locations of active seafloor spreading centers and the study area. (B) Detailed map of the study area (ship-based multibeam data acquired during cruise MSM109) including the Brøgger Axial Volcanic Ridge (AVR) and the newly discovered active hydrothermal area called the Jøtul hydrothermal field. (C) AUV-based bathymetry of the Jøtul hydrothermal field (data obtained during cruise MSM109 and provided by the Norwegian Offshore Directorate). Track lines of the ROV dives are shown and parts of the tracks where hydrothermal activity has been visually observed are marked in yellow. Four sites were sampled for fluids during MSM109 and are indicated by circles. Credit: Scientific Reports (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-024-60802-3

“The Jøtul field is a discovery of scientific interest not only because of its location in the ocean, but also because of its climatic importance, which was revealed by our detection of very high concentrations of methane in fluid samples, among others,” reports. Gerhard Bohrmann.

Methane emissions from hydrothermal vents indicate a strong interaction of magma with sediments. During its journey through the water column, much of the methane is converted to carbon dioxide, which increases the concentration of CO2 in the ocean and contributes to acidification, but also has an impact on climate when it interacts with the atmosphere.

The amount of methane from the Jøtul field that eventually escapes directly into the atmosphere, where it then acts as a greenhouse gas, still needs to be studied in more detail. Little is also known about the organisms that live chemosynthetically in the Jøtul field. In the darkness of the deep ocean, where photosynthesis cannot occur, hydrothermal fluids form the basis for chemosynthesis, which is used by very specific organisms in symbiosis with bacteria.

To significantly expand the somewhat sparse information available on the Jøtul Field, a new MARIA S. MERIAN expedition will begin in late summer this year under the leadership of Gerhard Bohrmann. The focus of the expedition is the exploration and sampling of the still unknown areas of the Jøtul field. With extensive data from the Jøtul field it will be possible to make comparisons with some already known hydrothermal fields in the Arctic province, such as the Aurora Field and Loki Castle.

The published study is part of Bremen’s group of excellence The Ocean Floor-Earth’s Uncharted Interface, which explores complex processes on the sea floor and their impacts on global climate. The Jøtul field will also play an important role as an object of future research in the Cluster.

More information:

Gerhard Bohrmann et al, Discovery of the first hydrothermal field along the 500 km long Knipovich Ridge offshore Svalbard (Jøtul field), Scientific Reports (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-024-60802-3

Provided by the University of Bremen

citation: Investigation of newly discovered hydrothermal vents at depths of 3,000 meters off Svalbard (2024, June 28) retrieved June 28, 2024 from https://phys.org/news/2024-06-newly-hydrothermal-vents-depths-meters .html

This document is subject to copyright. Except for any fair agreement for study or private research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.