NASA has a backup astronaut waiting for the first human mission to the moon in more than 50 years, which will lift off no earlier than 2025.

NASA astronaut Andre Douglas will serve as a backup to three American astronauts on the Artemis 2 lunar orbiter, the agency announced today (July 3). Douglas will support Commander Reid Wiseman, Pilot Victor Glover and Mission Specialist Christina Koch. Canadian Space Agency (CSA) astronaut Jeremy Hansen, who is also a mission specialist on Artemis 2, already has a backup: astronaut Jenni Gibbons, also with CSA.

Connected: New NASA astronauts celebrate moon missions, private space stations as they prepare for liftoff (Exclusive)

“I’ve always been fascinated with new things. I like to develop things,” Douglas told Space.com in March about the Artemis program, which later this decade aims to put astronauts on the surface of the Moon for the first time since since 1972. I really believe in pushing ourselves, in realizing what our true potential is: as myself as an individual, [and] within all of us as a species”.

“This is the perfect place to be, where we’re going to push that boundary,” he said.

Douglas was selected as an astronaut candidate by NASA in 2021 and graduated to full astronaut status in March of this year after completing his training. Prior to joining the agency, he served in the US Coast Guard in multiple roles and earned several post-doctoral degrees in technical fields ranging from naval architecture to systems engineering.

Immediately prior to astronaut selection, Douglas was a senior professional staff member at Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) working on several high-profile space missions. “That was a favorite past time,” Douglas said.

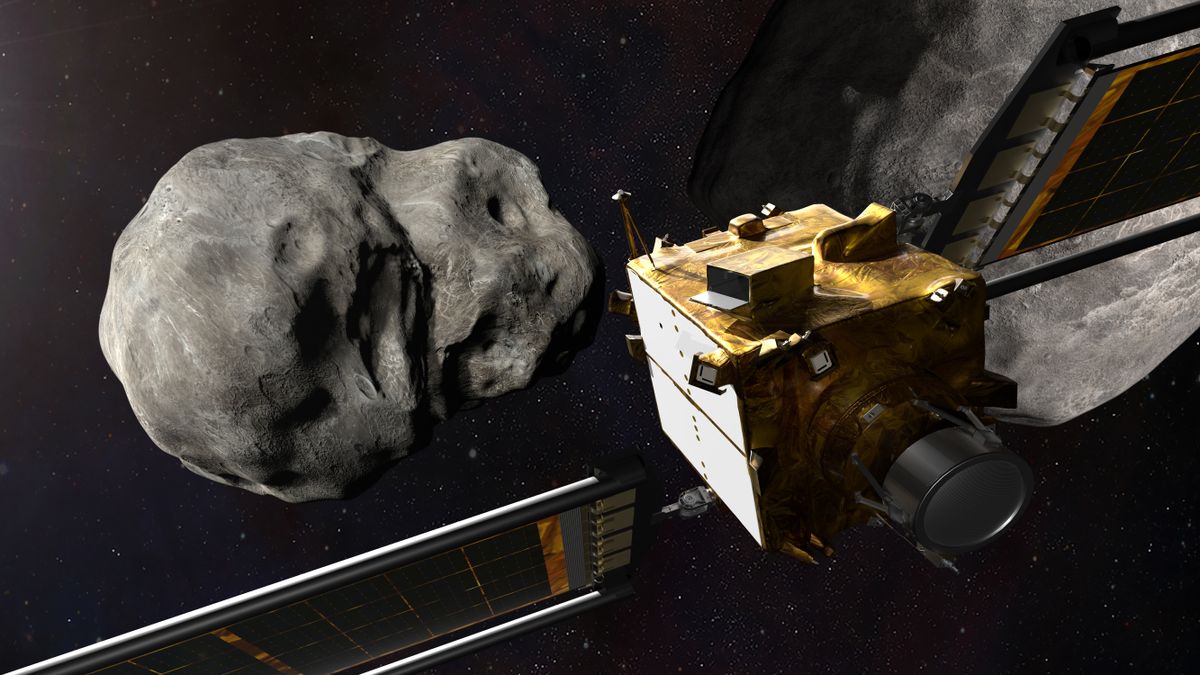

He was an error management engineer, for example, on NASA’s Dual Asteroid Redirection Test (DART). The historic mission was the first to successfully change the orbit of an asteroid moon around a larger space rock after a deliberate collision in 2022.

“I was writing the scripts of a software project to help deploy the spacecraft in a safe manner if something went wrong,” Douglas said, noting that the mission was “pretty awesome” as it demonstrated that the kinetic planetary defense against hazardous asteroids is potentially feasible.

In addition, Douglas worked on a large instrument for the Martian Moons Exploration (MMX) mission, scheduled to fly to the Red Planet in late 2026. The instrument is called MEGANE (Mars-Moon Exploration with Gamma Ray and Neutrons) and will to support a Mission goal to learn the composition of Phobos and Deimos, the two moons of Mars.

Connected: Helping build instrument for Japan’s Mars mission ‘a favorite time’ for new NASA astronaut (exclusive)

In May, Douglas even tried moonwalk simulations in the field: He worked for a week at the San Francisco Volcanic Field near Flagstaff, Arizona, along with NASA astronaut Kate Rubins, to test updated spacesuits in the area of the desert like the moon by day and by night. the conditions.

“Andre’s educational background and extensive operational experience in his various jobs prior to joining NASA are clear evidence of his readiness to support this mission,” said Joe Acaba, chief astronaut at the Johnson Space Center. of NASA in Houston, in the agency’s statement on the Artemis 2. backup selection.

“He excelled in his astronaut candidate training and technical duties,” Acaba added, “and we are confident he will continue to do so as NASA’s backup crew member for Artemis 2.”

Artemis 2 draws on a diverse set of experiences in its crew: Glover, Koch and Hansen will be the first black, woman and non-American to orbit the moon, respectively.

Earlier this year, the mission’s liftoff was pushed back nine months to September 2025 to account for additional testing on the heat shield, among other critical items. Artemis 3, a landing attempt, is expected no earlier than 2026.

In interviews with Space.com in May, three of the Artemis 2 crew members (Koch was not available) emphasized that development missions must move at the pace of safety and learning, and that rendezvous schedules are not the goal.

“At the end of the day,” Hansen told Space.com at the time, “I think it’s also important to realize that we’re never going to be able to make this risk zero. We’re going to learn everything we can in the facilities our testing, and [in what] science can reach the ground. And then at the end of the day, we will still have an unknown risk that we will have to accept.

“But that’s part of space exploration.”