This infographic highlights how much data and how many images NASA’s 2001 Mars Odyssey orbiter has collected in its 23 years of operation around the Red Planet. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

NASA’s longest-lived Mars rover will hit a new milestone on June 30: 100,000 trips around the Red Planet since launch 23 years ago. During that time, the 2001 Mars Odyssey orbiter has mapped minerals and ice across the Martian surface, identifying landing sites for future missions and relaying data back to Earth from NASA’s rovers and landers.

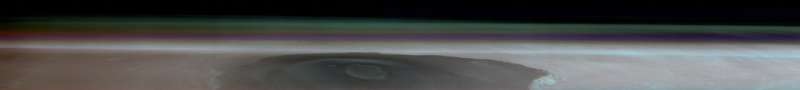

Scientists recently used the orbiting camera to take a stunning new image of Olympus Mons, the tallest volcano in the solar system. The image is part of an ongoing effort by the Odyssey team to provide high-altitude views of the planet’s horizon. (The first of these images was released in late 2023.) Similar to the view of Earth astronauts boarding the International Space Station, the view allows scientists to learn more about the clouds and dust in the air on Mars.

Taken on March 11, the latest image of the horizon captures Olympus Mons in all its glory. With a base that stretches 373 miles (600 kilometers), the shield volcano rises to a height of 17 miles (27 kilometers).

NASA’s 2001 Mars Odyssey orbiter captured this single image of Olympus Mons, the tallest volcano in the solar system, on March 11, 2024. In addition to providing an unprecedented view of the volcano, the image helps scientists study layers variety of material in the atmosphere, including clouds and dust. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASU

“Normally, we see Olympus Mons in narrow bands from above, but by turning the spacecraft toward the horizon, we can see in a single image just how big it looks over the landscape,” said Odyssey project scientist Jeffrey Plaut. of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in the south. California, which manages the mission. “Not only is the image spectacular, but it also provides us with unique scientific data.”

In addition to providing a frozen frame of clouds and dust, such images, when taken over many seasons, can give scientists a more detailed understanding of the Martian atmosphere.

A bluish-white streak at the bottom of the atmosphere hints at how much dust was present at the site during early fall, a period when dust storms typically begin. The purple layer above it is likely due to a mixture of the planet’s red dust with some bluish water-ice clouds. Finally, at the top of the image, a blue-green layer can be seen where water-ice clouds reach up to about 31 miles (50 kilometers) into the sky.

How did they take the picture?

Named after Arthur C. Clarke’s classic science fiction novel “2001: A Space Odyssey,” the orbiter captured the scene with a heat-sensitive camera called the Thermal Emission Imaging System, or THEMIS, which Arizona State University in Tempe built it and it works. But because the camera is meant to look at the surface from below, taking a shot at the horizon requires extra planning.

By firing thrusters located around the spacecraft, Odyssey can guide THEMIS to different parts of the surface or even slowly rotate to view Mars’ small moons, Phobos and Deimos.

The last images of the horizon were conceived as an experiment many years ago during the landings of NASA’s Phoenix mission in 2008 and the Curiosity rover in 2012. As with other Mars landings before and after those missions landed, Odyssey played a important role in transmitting data as spacecraft barrel toward the surface.

To transmit their vital engineering data to Earth, Odyssey’s antenna had to be pointed at the newly arrived spacecraft and their landing ellipses. Scientists were intrigued when they noticed that the positioning of Odyssey’s antenna for the task meant that THEMIS would be pointed at the planet’s horizon.

“We just decided to turn on the camera and see what it looked like,” said Odyssey mission spacecraft engineer Steve Sanders of Lockheed Martin Space in Denver. Lockheed Martin built Odyssey and helps run day-to-day operations alongside mission managers at JPL. “Based on those experiments, we designed a sequence that keeps THEMIS’ field of view centered on the horizon as we orbit the planet.”

The secret of a long space odyssey

What is Odyssey’s secret to being the longest continuously active mission in orbit around a planet other than Earth?

“Physics does a lot of the hard work for us,” Sanders said. “But it’s the subtleties that we have to manage again and again.”

These variables include fuel, solar energy and temperature. To ensure Odyssey uses its fuel (hydrazine gas) sparingly, engineers must calculate how much is left since the spacecraft does not have a fuel gauge. Odyssey relies on solar energy to power its instruments and electronics. This power changes when the spacecraft disappears behind Mars for about 15 minutes in orbit. And temperatures must stay balanced for all of Odyssey’s instruments to function properly.

“It takes careful monitoring to sustain a mission this long while maintaining a historic timeline of scientific planning and execution — and innovative engineering practices,” said Odyssey project manager Joseph Hunt of JPL. “We look forward to collecting more great science in the years to come.”

citation: NASA’s Mars Odyssey Orbiter Captures Large Volcano, Approaches 100,000 Orbits (2024, June 27) Retrieved June 27, 2024, from https://phys.org/news/2024-06-nasa-mars-odyssey -orbiter-capture.

This document is subject to copyright. Except for any fair agreement for study or private research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.